February 6, 2019

Advice fees but no service: a question of criminal law

The threat to vertical integration has receded but financial advice is under attack. Ongoing fees underwrite the...

By investigating practices implicit in vertically integrated business models, the Australian Royal Commission report is likely to ask serious questions of the wealth management industry: UK wealth managers need to take note.

In early February a seminal report into misconduct in the wealth management industry is expected to be released which is likely to have profound consequences.

Since December 2017, an Australian Royal Commission has been investigating the banking, superannuation (pension scheme), and financial services industry, seeking out misconduct, conduct falling below community standards, and misuse of retirement savings. As the name suggests the remit has been broad, but some of the biggest impacts have been in the wealth industry, particularly relating to financial advice.

Even before the publication of the interim report last September, the Commission’s hearings had cut a swathe through the Australian wealth industry. It has already ended careers of numbers of senior executives, CEO, and board members, raised the possibility of criminal charges being laid, and contributed to the destruction of conservatively £5 billion in market value.

Australia may be an island – albeit a big one – but it’s a globally significant pensions market. It is often looked to for lessons learned – good and bad – by market participants and regulators elsewhere. For UK market participants, where vertical integration (VI) has returned to the wealth industry in a range of models, there are some important warning signs to consider before the FCA does.

Key questions for UK

The final report will no doubt be lengthy, complex, and wide-ranging. However we see two critical questions emerging which are just as relevant for the UK wealth industry:

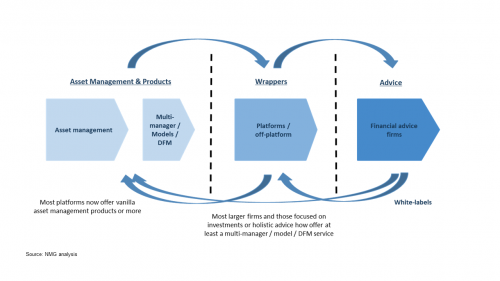

VI has been increasingly prominent in the UK over the last few years, in two distinct guises: (Figure 1):

Figure 1: UK vertical integration trends

Pros and cons of vertical integration

VI is not fundamentally a bad thing for consumers. Wealth products and services are complex and many consumers experience information asymmetries. VI can allow a market participant to offer more complete services and a better experience via a “walled garden” of quality-vetted solutions. In an industry value chain where certain activities are highly valued or under-valued by customers relatively to their cost of delivery, VI can also be a relatively efficient way of reallocating value more evenly across activities.

Given that consumers often are not prepared to pay much for advice, platforms generally experience low margins, but asset management enjoys high margins, there are also strong financial incentives for different market participants to vertically integrate. Advice and platform owners have an incentive to move into asset management, and asset managers and platform owners have an incentive to offer advice providers a slice of the margin action.

That’s at the heart of the trouble. How do you protect consumer / client interests when advice providers have direct or indirect access to product economics in the form of access to bps revenues or salary bonuses linked to sales volumes?

There’s a high risk that the Commissioner will conclude that it can’t be done – that the conflicts of interest inherent in these arrangements cannot be managed and that governance frameworks do not actually work in practice. The interim report posed a set of key questions:

Those questions have been on the table since last April and have not gone away. If anything the accumulation of evidence has magnified them.

Routes to non-conflicted models

While it might take some time for implications to become apparent in the UK, vertical integrators should get ahead of the curve – starting with answers to the above questions. NMG has assessed some practical routes to non-conflicted models, including advice KPIs based on NPS and other customer measures, charging for advice on a standalone cost plus margin basis, and demonstrating an equitable sharing of VI value – not just benefits – with customers.

VI creates the scope for more conflicts of interest, but a non-vertically integrated industry structure doesn’t necessarily result in better outcomes for the client. The right VI model can put the UK wealth participants on a more sustainable financial footing – and better placed to deliver for the customer – so long as they remember whose interests come first and avoid the excesses of the Australian industry, which have finally come home to roost.

For more information, contact:

Andrew Baker, Partner (London; [email protected])

Evan Baars, Senior Consultant (London; [email protected])