Member disengagement in workplace pensions is well documented; with similar issues evident in individual pensions, providers need to be smart but realistic in their communications strategy.

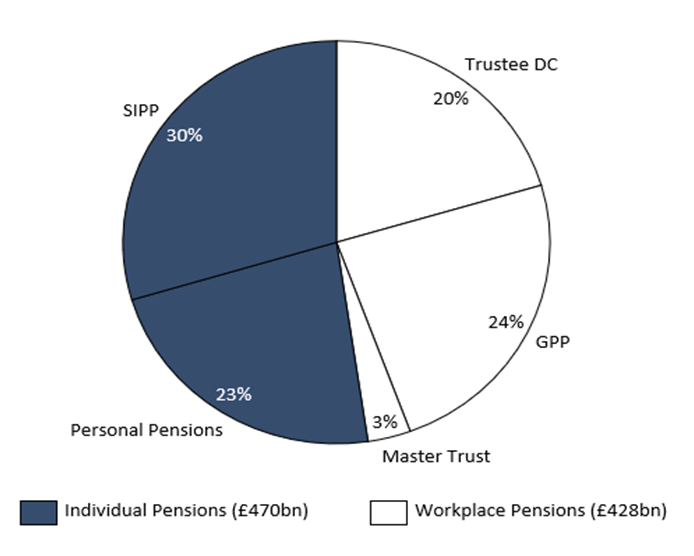

Despite the recent focus on engagement issues within workplace DC pensions, it is worth remembering that individual pensions (personal pensions and SIPPs) still account for >50% of DC pension assets – some 12m accounts with AUM valued at more than £470bn.

FIGURE 1: UK DC PENSION AUM ~£898BN 2018

Source: NMG Consulting

The FCA’s recent feedback paper on non-workplace pensions therefore makes fairly bleak reading. It examined consumer behaviours and decision making, both at product purchase and ongoing, as part of its investigations into the effectiveness of competition in this market. The report found demand-side weaknesses with striking similarities to the workplace pensions market.

How bad is disengagement within individual pensions?

NMG’s qualitative research performed for the report interviewed 73 individual pension investors, spanning those with long-standing, older products to those with recently acquired SIPPs on platforms, both advised and non-advised. The research sought to understand their engagement with their non-workplace pension products, including motivations, buying decisions, ongoing needs and product experiences. Engagement in our report is defined as: ‘interest and involvement in the non-workplace pension, where involvement is a positive decision to do, or not do, something in relation to their pension.’

The findings are a stark reminder that fundamentally, people:

- Place pensions low down in their hierarchy of needs

- Rely on life events or push from influential others to trigger pension research

- Find pensions complex and confusing

- Display irrational pension purchasing behaviour or outsource pension purchase altogether

- Prefer to forget about pensions over the longer term

NMG’s research highlighted that even among individual pension investors, appreciation of the need for a pension is low. Only a minority of consumers perceive a strong need for pension provision at time of product purchase. Among these customers, higher engagement is evident, driven by better understanding of the benefits of pension planning.

Why is engagement at time of purchase poor?

There are several reasons why consumers become disengaged when purchasing a pension.

- Complexity of pension products and the time / effort required to gain knowledge for effective decision making is seen as unattractive, so consumers tend to delegate decision-making to trusted others (in the absence of an adviser, this is typically dad, the boss or a ‘knowledgeable’ friend) or simply rely on a well-known brand.

- Many triggers for pension purchase (leaving a job, changing life stage) occur at a time of flux, meaning the purchase is often done with a highly short-term ‘get-it-sorted-and-forget-about-it’ attitude.

- Nudges from influential others (adviser, parent) can mean the importance of long-term pension planning can be missed. It is simply interpreted as ‘the sensible thing to do’.

Even consumers conducting their own research face challenges to their engagement, due to the complexity of pensions:

- Regulation / taxation complexity means consumers struggle to understand the technical benefits of pension savings vs other product wrappers (e.g. ISAs)

- Product complexity means consumers struggle to differentiate between products (SIPP vs Personal Pension) and product features of comparable providers

- Charging complexity means consumers struggle to compare pension providers on a fee basis

Complexity drives disengagement in two ways. First, it drives behavioural short-cuts or ‘heuristics’, overriding rational buying behaviour such as choosing on a comparison of price or features. Only in a minority of cases were more criteria used to assess pension providers and products, and even then, criteria are typically limited to fund choice, flexible features and security of the provider. Price is rarely a lead driver of selection, a fundamental barrier to the FCA’s desire to improve competition on this metric.

Second, comparability of complex features and charging structures can make shopping around too hard, so many consumers delegate decision-making to trusted others.

Poor engagement levels at time of purchase lead to even lower levels of ongoing engagement. Most leave the pension to accumulate without thinking too much about it, particularly in the absence of advice and/or ongoing contributions. The severity of disengagement is highlighted by just half of our sample reading last year’s pensions statement.

The results of this ongoing disengagement can be critical, for example, consumers with older products unaware if their charges are competitive or if savings could be made by switching.

What can be done to encourage engagement?

Without stronger calls to action, there will be little ongoing engagement, and by implication, no review or switching. Respondents are hugely reliant on their pension provider(s) and adviser to understand their pension and see if they are on track, but as things stand effective touchpoints with providers are few, and many consumers who initially purchase on an advised basis disconnect from their adviser over time.

Individual pension providers seeking to improve engagement need to be realistic about this landscape and work with it, rather than hope for utopian outcomes. Key planks to a realistic approach include:

- Target consumers who want to engage – among some consumers there is a latent desire for providers to engage more, to remind and reinforce the benefits of pension saving and to educate on the basics – an almost guilty acknowledgement that most need to do more.

- When you engage, engage early, and seek just one small positive change – small actions taken early have enormously beneficial long-term impacts.

- Talk about outcomes, not product – most consumers find pension products dull, but they are able to understand the importance and tangible benefits of saving for retirement.

- Hope for engagement but don’t assume it – address the majority that don’t and won’t engage by enhancing features that work with non-engagement. Simple products, simple pricing structures, default pathways, and easy access to advice and guidance – if they want it – will create better outcomes for consumers in their use of pensions.

Ultimately, engagement is important and should be encouraged and supported with consumer-friendly tools and regular comms to nudge and remind. But, as seen in workplace pensions, it’s just as important that consumers can be disengaged and still secure good outcomes.

For more information, contact:

Jane Craig, Partner (London; [email protected])